ART AND US

La Tribune de Tanger, Morocco, May 1951

|

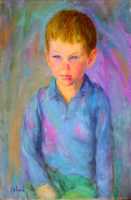

Little

Boy Blue

by Jean Tabaud

(See Artwork H-29) |

I remember when I was about twelve years old I spent hours watching

a painter at a seaside resort working out of a kiosk in all kinds

of weather blithely ignoring the crowd of spectators looking on. He

had an Olympian belly, and with a cigarette butt dangling from a corner

of his lips, he would take a brush and tock, tock, tock, rapidly dab

red paint on three different canvases, one next to the other. Then

it was a green paint brush, then white, etc. Or he would paint a bouquet

of poppies. Or it could be a rock in a blue sea, creating three perfectly

identical paintings as he worked. All this before the astonished eyes

of the onlookers, dressed in their customary blazers and straw hats.

In the evening, these canvases would be sold at auction before a very

animated crowd of people. After the seascapes were sold came a large

series of paintings of cats playing with a ball of yarn. Then there

were those of a Cardinal seated by the corner of a fireplace, his

face benignly illuminated by the burning logs, and with a bottle of

burgundy within easy arm's reach. Such tender winter scenes easily

erased, in everyone's mind, mine included, the powerful odor of vanilla

in the air, coming from the nearby waffle vendor's booth, or the sound

of the nearby waves beneath the starry August sky above! Anyone who

made fun of this daily event would risk having his straw hat jammed

down on his head hard enough to reach his tie.

Later, as a teenager, I visited museums and, like everyone else,

I stood respectfully before each masterpiece, moving slowly from one

to another. Even the most blackened and smoke-damaged canvases filled

me with admiration. It was only later that I began to distinguish

the difference between veneration and love. In any event, I left the

Louvre firmly in the grip of these initial feelings.

These two vivid memories, among many similar ones, stayed with me.

I would not deny to anyone the sincerity of the emotions I experienced:

the fullness, the warmth of those moments, and the contentment, the

inner peace, they filled me with, whether they were legitimate, justifiable

feelings or not. Such pleasures, such joys stay with one forever.

The farther away I go from my mother's house, the more I long to once

again see the canvas hanging on the wall of the dining room since

I was an infant. Little kittens playing in a fruit bowl. I would prefer

to find it there rather than a Braque or a Matisse. When I was sixteen

or twenty years old, in a moment of excess zeal, I thought of replacing

it with something better. But I was dissuaded by my grandmother who

did not want to have her two little kittens replaced by something,

in her opinion, that was absolutely outlandish.

Trouble begins (the devil steps in) when people become aggressively

critical (point their umbrellas at) modern painting. When tolerance

disappears, theorists become dogmatic. And theorists, in art as in

politics, have only the ability to convince. One agrees or one does

not. Such thinking is an affair of the mind and of our culture, whereas

art is, first of all, a question of temperament.

If one decides that painting is more of an action media than a delicate

way of passing the time, one must admit that this requires, like all

major actions, an enterprising spirit and a certain amount of courage.

The real artist, even if he doesn't know it, is a pioneer, like all

adventurous men who engage in the search for virgin places. Isn't

art the need to escape from the daily, habitual routine of life? In

a crowd of men there will always be the majority of whom live their

lives in the reassuring shadow of routine, while only a few will explore

the unknown.

Sometimes the practice of art produces nothing more than a delightful

feeling, as does a peaceful siesta after dinner. Or it can be as shocking

as a winter bath in a glacial sea.

But art that is pleasurable to the eye, can also have many disconcerting

aspects. For instance, a landscape by Bonnard, obviously oscillating

between happiness and sensuality, can be disconcerting to the general

public with its quivering polychromes, where the cloud can be Prussian

blue and the tree rose-colored. Just as music, which delights the

Chinese, can make many of us grind our teeth.

All depends upon what we are accustomed to. Art has nothing to do

with logic. In a Corot landscape, for instance, the air which is circulating

among the leaves directly touches our senses by a phenomenon, which

seems very simple to us. But which is not as strong as the emotions

we feel when viewing the impressive geometry of the pyramids, or a

mysterious Polynesian idol. The senses are immediately shocked - and

whether they are intrigued more than pleased - they need time to adapt,

as does the retina of the eye when it passes from shadow to light.

One can say that at the height of civilization, when the mind (the

spirit) reaches its full potential, is when art weakens. Cultural

growth levels off by stifling man's deep profound feelings, which

are governed by his purely physical nature. But the refinement of

taste, the realization of scientific achievements, the societal stamp

of approval on his feelings, lead, little by little, to a form of

original art, wherein fervent doubt takes the form of mystery as it

represents something definite, positive, before the Appellate Court

(of art). Without a doubt, for the first time in our civilization,

artists have begun to follow the road of this natural turn of events

and come back to the elements of art. Or they simply change things

around in order to once again infuse life into art as it was in the

beginnings of mankind - in order to fulfill their role as executors

of the legacy that the first "primitive" artists left to

their trust.

Does this signal intellectual despair? Esthetic guile? Or for some,

resurrection? Who cares how many believe in the inspired isolation

of some, their return to the source, and the convoluted perspective

of willing followers…..? This mixture of feelings occurs in all

intellectual movements. Christopher Columbus, the great adventurer,

the only visionary among a crew of men paralyzed with fear and a thirst

for gold, discovered America, yet he started out searching for India.

Cézanne, who wanted to "redo Poussin and draw from nature,"

patiently gave his masterpieces to the world, which were vigorously

maligned by art critics. Thus he created a revolution in the art world,

which led to cubism. All the equipment that Cézanne used to

accomplish this revolution was a little compass that he called his

modest "feelings." That mankind uses an easel or a caravel,

these two instruments can be said to have led to equally world-shaking

achievements. Columbus died in misery, and Gauguin like an animal

in a Tahitian straw hut. I can take little comfort, therefore, in

the wise words of Elie Faure: "Ingratitude toward great men is

the sign of great people."

Jean Tabaud