|

|

Introduction

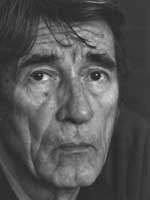

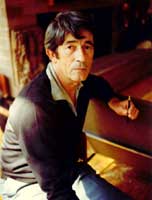

photo by

Bob

Willoughby |

|

Jean

Tabaud at 42

|

The

following summary of Jean Tabaud's life is based on my forty-year

friendship with

him, which began in Hollywood in 1956, and which lasted until his

death in 1996. It is based on tales he told me, on letters he wrote

to me, on the four manuscripts he left behind (three autobiographical

novels and one memoir), on numerous newspaper articles he authored,

on interviews he gave, on appointment agendas, and diaries he kept,

albeit haphazardly, throughout the years. As well as on other bits

and pieces of information about his life that I found among his

papers, which I inherited as the executor of his estate. He also

left in my care some 300 paintings, drawings, and sketches. And

hundreds of photos of portraits he executed during his lifetime,

some identifiable, but most are not. A few of these can now be viewed

on this website. More will be posted as this site expands.

There

were years when Jean and I didn't see each other. When he was either

traveling in Europe or in various parts of the United States, and

when I was also living in other parts of the world and on other

continents. But we always managed to stay in touch, no matter what

the circumstance. At the very least, a few letters a year passed

between us, even when I was caught in the turmoil of the Congo's

independence from Belgium in 1960. Or, subsequently, when I was

farming on the remote pampas of Argentina and Jean had become a

prominent portrait artist with studios in New York, Paris, St. Moritz,

London, San Francisco.

Beginnings

Jean

Tabaud was born Jean Gilbert Tabaud on July 5, 1914, in the small

town of Saujon, France, on the Southwest Atlantic coast, north of

Bordeaux. He was the son of Lucien Tabaud and Ernestine Tabaud Hillairet.

His father was a butcher by profession, who served in World War

I, where he was wounded and gassed during the conflict.

Jean

remembered his early childhood as being a happy one, helping his

father in his butcher shop. And, when he was old enough, served

as his delivery boy, riding about the countryside on his bicycle,

delivering his father's meats and homemade sausages to the housewives

in the area, who never failed to reward him with a sweet or two.

As an only son, he was adored by his parents, and when not attending

school or helping out in the shop, was allowed to roam as he pleased

over the landscape of the Charente River where it empties into the

Atlantic. Jean had a free, good-natured spirit, an open, candid

smile, sparkling black eyes that exuded good humor and which never

failed to elicit a smile in return from those he met, friend and

stranger alike. He loved to run in the fields and jump walls. He

longed to fly like a bird.

By

the time he was ten, however, his father could no longer support

the pain caused by his war wounds. One evening he invited Jean to

a local restaurant for a celebration dinner, as he called it. When

they returned home, he took off the four-banded gold ring that wound

around the third finger of his left hand in the form of a snake

and handed it to Jean, telling him, "Always wear this. It

belonged to your grandfather and his father before him."

Then he embraced his son, climbed back into his car, and put a bullet

in his head.

Despite this traumatic heartbreak,

Jean's optimistic outlook on life continued. His spirit remained

a free one; his appreciation of nature's beauty, and his adoration

of the human body as a sublime creation, especially the female figure,

never ceased to fill him with wonder.

|

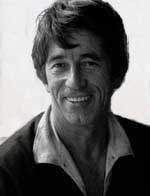

| Jean

Dancing |

Following

his father's death, Tabaud's formal education came to a halt. In

his teen years he earned his living selling brooms from door to

door, apprenticed as a picture framer, dabbled in journalism, and

at nights worked as a cloak-room attendant at "La Forge,"

a music hall in nearby Bordeaux. He often wandered backstage, observing

the dancers and envying them their graceful agility, imitating their

routine whenever he could. It was there that he met the famous Belloni,

husband and wife team, who encouraged him to study classical dance

for a year, following the rigorous Cecchetti method. Then the impresario

Lifar came into his life. His first engagement, at the age of 20

in 1934, was with the Comédie Française. Later he

would dance with the Marquis de Cuevas' Grand Ballet Company, and

soon was invited to join the Ballets Russes.

While in Paris he met several artists

- friends of the theatrical crowd with whom he associated. Among

those who particularly impressed him was the Polish artist, Maïa

Berezowjka, and recognizing his natural talent, she encouraged him

to study art. He attended a few classes at the École des

Beaux Arts but he had little time for this as his ballet career

developed into full-fledged stardom for him with the Ballets Russes,

dancing in Paris, Berlin, Geneva, Belgium, Switzerland, Rio de Janeiro,

Tangiers, Casablanca, and Argentina.

But

while performing at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires in 1939, he

fell while practicing a particularly difficult dance maneuver, injuring

his spine, and forcing him to give up dancing. He returned to France

to seek treatment for his back but instead met up with the outbreak

of World War II. He was immediately drafted into the French Army,

witnessed the fall of France to Germany, and was taken prisoner

in 1941.

Yet, despite the hardships he suffered,

his ever-present back pain, and the horrors he witnessed, his good

humor and blithe spirit remained intact to the point where his fellow

war-weary prisoners knick-named him "Simplicimus" - the

simple one.

While in the camp, he managed to procure

some paper and crayon, and, to pass the time, began sketching portraits

of his fellow prisoners. One of the German guards, observing this,

asked if he, too, could have his portrait done. The result was so

pleasing to him that soon other guards, as well as the Commandant

of the camp, asked for the same and supplied Jean with all the drawing

materials he needed.

|

| German

Soldier |

One day

in 1942, Jean seized the opportunity to leave the camp, along with

a group of other prisoners, who were assigned to assist local farmers

to bring in the harvest. But he never returned with them. He quietly

slipped away and made his way to Paris, where he found friends who

supplied him with false identity papers. For the next two years

he made his living as a peripatetic artist, in the evenings going

from one café to another, drawing portraits of German soldiers,

sailors, airmen of all ranks, charging but a few francs each. He

plied his trade not only in Paris but traveled to the Normandy coast

and Le Havre - often on bicycle. He returned to Bordeaux, visited

his mother in nearby Saujon, and then went on to Marseilles, Nice,

and the south of France. Then he returned to Paris, always using

the same false identity papers. All the portraits he executed during

this time had to be signed with the name they bore: Juvee.

While

plying his trade at night, Jean sought help for his back during

the day from several Parisian doctors, but without success. Yet,

he continued to practice his classical ballet exercises. Painting

was just a way of earning a living for him until he would be well

enough to resume his dancing career. In 1943 Jean was invited to

join a French troupe, which was asked to perform in Berlin. His

pain was almost unbearable but he managed to execute the most perfunctory

of steps. Soon, however, the bombing became intense, the ravages

of war all about them intolerable, and the company shortly limped

back to Paris.

Meanwhile, Tabaud lived constantly

with the fear that his escape from the prison camp would be discovered.

But the Germans evidently believed he was harmless enough, never

dealing in the black market or suspected of being a member of the

underground. He was useful to them. His subjects ranged from lowly

seamen to high-ranking officers, most choosing to be portrayed in

full uniform, but some did not. Toward the end of the war, Tabaud

was recruited by a German doctor to do the portraits of wounded

and dying soldiers in the Paris hospitals. He preferred these assignments

above all others. These portraits were then sent to their families

back in Germany.

By

the time of Germany's defeat, Tabaud had executed over 5,000 portraits

between 1942 and 1944. During this time he managed to secure a camera

and took photos of the portraits he had done to show to potential

clients. Ninety-five photos of these portraits have survived and

several examples can be seen on this website.

Tabaud

was in Paris when the Germans marched out and the U.S. troops marched

in. This extraordinary period in his life is recorded in detail

in his French memoir of the war years titled, Une Couche de Vie

sur une Tranche d'Histoire. Roughly translated: A Layer of

Life upon a Slice of History.

He remembers having witnessed the

following scene in August 1944, two months after the Allied Forces

landed in Normandy. "In the afternoon I awoke,"

he wrote, "and headed toward the Place Blanche in search

of something to eat. The streets were deserted. All of Paris was

hiding behind shuttered windows and doors, waiting for the Americans

to arrive, terrified by the rumor that Paris had been mined and

would blow up before we were saved. As I turned the corner, I was

astonished to discover a tide of Germans, as far as the eye could

see, filling the boulevards, flowing slowing, silently, upstream

and downstream, like a river."

It was at this time that Jean, forced

to remain secluded in his apartment with his mistress, existing

on only flour and water, drew his first nude. (Nudes would become

one of his favorite subjects from here on and would greatly contribute

to his fame as an artist.)

Then,

Jean's memoir continues, "…It took several more days

for them (the Americans) to arrive, but first came de Gaulle, marching

triumphantly down the Champs Elysées at the head of his Free

French troops…and this time all of Paris was there to greet him…

"The

Americans followed the next day. I was thunderstruck by what appeared

before my eyes: a mass of miserable corpses, mute, silent, surrounded

on all sides by jubilant crowds. They came wearing tattered uniforms

the color of dead leaves. Coming so soon after the stony, granite-like,

impeccably dressed Germans, one would think the Americans fought

the war in their pajamas. And wearing slippers. For if it weren't

for the tanks that accompanied them…one would not take them

for soldiers at all. They marched with a soft step and waddling

gait - barely a military one - in rubber heeled shoes. They did

not make more noise than a caravan of camels."

Morocco, Hollywood,

Mexico

|

| Jean

in Holllywood with a drawing of Jossee, his favorite model,

in the background |

Following

the end of the war, almost one year later, Tabaud, seeking the sun

and escape from war-torn Europe, traveled to Majorca and then to Morocco,

where he lived for eight years. In Tangiers and Casablanca he established

a school of dance, gave recitals, choreographed ballets, wrote articles

on art and the

dance. During this period he painted many Moroccan landscapes, as

well as studies of the local people. In 1953 he was encouraged to

try his luck in the United States.

He

began in Hollywood, where he was immediately successful, receiving

commissions for portraits from such stars as Charles Boyer, Deborah

Kerr, Pier Angeli, "Zizi" Jeanmarie, to name a few. The

French Ambassador to Mexico, while visiting Hollywood, suggested

an exhibit of his works - particularly his Moroccan landscapes -

in Mexico City. It was met with considerable success and was followed

by two more exhibits. One in Monterrey and one in Acapulco.

New York

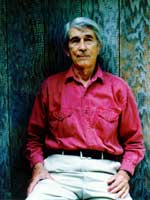

|

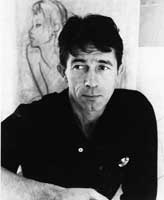

Jean

at 56 (1970)

working in his Pauling studio |

Following

several more critically acclaimed exhibits in Los Angeles and San

Francisco, Tabaud moved to New York City in 1957, where he established

his studio at 440 East 79th Street. Over the next ten years he traveled

extensively, executing portrait commissions in the United States

|

Mrs.

John Y. Randolph Crawford

New York, N.Y. |

and Europe of the rich

and famous, as well as the not so

rich nor famous. Among his innumerable clients

were such subjects

as the Mrs. Henry Fords, (both Anne and Christina) as well as Henry

Ford's children, Anne, Charlotte, and Edsel. Mrs. Ted Kennedy, Mrs.

Stavrous Niarchos (Eugénie) and her children. Mrs.Pierre S.

DuPont, Jr., Henry Miller, Lady Sarah Russell, Lady Sarah Crichton

Stuart, Mrs. T. Jefferson Coolidge, Mrs. Clint Murchison, Jr., and

her daughter. Suzy Parker, Peter and Lili Pulitzer and their children,

Mrs. John Warner (daughter of Paul Melon) and their children. John

Kenneth Galbraith, Baroness Fiona von Thyssen, Mrs. Howard Cushing,

Jr., and her children.

|

| Pyramid

Man |

In

addition to portrait painting, Tabaud experimented with various

schools of art, most notably cubism, and with several different

techniques, such as oil on canvas as well as on board, colored pen,

water colors, pastels, charcoal and pencil, melted crayon with scratched

pen technique, etc. He was strongly influenced by the artists of

the impressionist era, especially Renoir, Monet, Corot, Van Gogh,

and later Modigliani. The influence of Gauguin can be detected in

his Moroccan paintings.

|

| Lady

L |

At

the height of his career, Tabaud executed several paintings under

the name of Leret, but was unsuccessful at marketing them. What

sold was a Tabaud. What clients wanted was a Tabaud and nothing

less. For several years he was featured in Portraits, Inc., in New

York in their annual exhibits of portraits by well-known artists.

His work appeared regularly in their New Yorker and other magazine

ads, as well in their New Year's greetings to their clients, featuring

the portraits he did of the founders of Portraits, Inc., - Lois

Shaw and Helen Appleton Read. These cards sometimes included the

portrait he did of Andrea Erickson Gehringer as well.

By

1968 Tabaud began to tire of the social life his portrait-seeking

commissions demanded of him, and he bought several acres of woods

outside the village of Pawling, New York, where he built his "hideaway."

Most of the house and outbuildings he constructed himself, but still

maintained his studio in New York City, to which he commuted three

days a week, and continued to travel to Europe for three months

out of the year, especially to France where he owned an apartment

outside of Versailles. In 1975 he made a trip to South America,

where he had commissions in Brazil.

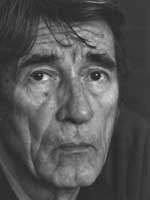

|

Jean

at 80 (1996) outside

his house in Pauling, NY |

He

also visited Argentina and the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, where,

thirty-six years before he had had his famous "mishap."

The pain in his back never left him. However, he continued to maintain

contact with the world of ballet, and kept himself in excellent

shape, exercising daily, and following a strict diet of organically

grown foods, supplemented by a wide range of vitamins. In Pawling,

he learned carpentry, built his own furniture, a sundeck for his

house, a woodshed, and a guesthouse hidden away deep in his woods.

Spring, summer, and fall he spent hours clearing the underbrush

in these woods and alongside the steep banks of the delightful,

fast-flowing, boulder-strewn brook that ran through his property.

He harvested his own wood, chopped, split, and corded it for his

fireplace, which burned brightly on chilly days and all through

the winter. If a visitor was lucky enough to be invited for dinner,

he, or most likely she - for Jean never wanted for female companionship

- would be treated to chicken roasted over this fire, and sometimes

a grilled steak.

He enjoyed observing the deer as they

came to feed in the meadow outside his picture windows, and, at

the same time, admiring the wild flowers that grew there in great

profusion. He was fiercely protective of these flowers, considering

them more beautiful than any cultivated rose and scolded the hapless

visitor who inadvertently happened to trample on them. "Please

don't walk on the wild flowers!" he would say. He refused

to use a lawn mower on his property.

It

was only in 1980 that he gave up his studio in New York altogether

and settled permanently in Pawling, traveling but once a year to

France to visit old friends. He had no family. He never had any

children. His mother and older sister - his only sibling - had died.

His closest relative had been her daughter with whom he had lost

touch years before. Jean Tabaud never chose to marry; although,

the number of mistresses in his life were many. There were few women

who could resist his natural charms. And his delightful French accent.

Even after fifty years in the United States, he never lost it. Although

from the French bourgeoisie, Jean had the manners of a highborn

gentleman, and treated each woman he met as though she, too, was

of royal blood.

I

came to the conclusion, after many years, that Jean loved all women

to the extent that he could never commit himself to any one woman

for life. After a period of observation, Tabaud could find something

special in the countenance of each one of his subjects, no matter

how poorly endowed by nature they might seem to the casual observer.

It was not unusual for a woman to exclaim upon completion of her

portrait, "I feel like I have just been made love to!"

In an interview with the New York

Times in 1966, Tabaud is quoted as saying that after he has painted

a woman he knows her better than do her friends of ten years. "To

paint," he said, "is an act of love whether the subject

is a tree or a woman. …A person who feels she is being loved

opens up and you get to know her."

In 1954 the Palm Beach Daily News

reported that "Tabaud makes his revelation of personality radiate

from the source of personal expression, the eyes of his subjects.

The individuality, then, shifts to the treatment of hair, the curve

of lips and, finally, is crowned with poetic precision by a pure

and thin contour line of exquisite delicacy."

|

| Mexican

Child |

Tabaud

also excelled in painting children. Though he never had any of his

own, he enjoyed painting them. The art critic of the Los Angeles

Examiner said in his review of one of Tabaud's exhibits in 1956,

"I am hard put to recall if I have ever seen more arresting

pictures. It has been three days since I looked at his works and

still their memory lingers in a most pleasing way. Especially the

portraits of little children. He gives their faces marvelous expressions:

as if they are, in a spiritual sense, on the threshold of adult

experiences, as if some unknown force is pulling their thoughts

into a world they would much rather back off from."

Retirement

In

Pawling, Tabaud pleased friends and neighbors by drawing their portraits,

free of charge. Whole days and evenings were spent reading the works

of philosophers whose thoughts he had longed wished to examine but

had never had the time to do so before. It was during this period

that he wrote his World War II memoir and completed the manuscripts

of three novels. All three of which sing praises of, pay homage

to, the beauty of the female form - page after page. Two years after

his death the Village of Pawling changed the name of the winding

dirt road leading to his home from Gristmill Lane to Frenchman's

Lane.

|

| Jean

Tabaud at 82 (1996) |

Jean

spent the last five years of his life battling Lyme disease. But

this debilitating disease was not diagnosed until three years before

his death, when treatment by antibiotics was of little use. By age

79, his hearing began to fail, as well as his eyesight. At 80 he

was diagnosed with cancer of the prostate and underwent major surgery.

This dealt a particularly fierce blow to his self-esteem. At 82,

having been fiercely independent all his life, he was denied a driver's

license. He feared the prospect of ending his days in a nursing

home, costing him most of his considerable, hard-earned fortune.

Thus he made the decision to will all his money to the Maryknoll

Catholic Missions in Peru, in care of my brother, Father Edmund

Cookson. "For the children," he told me and his lawyer,

"where it will do some good."

In the last letter he

ever wrote, dated December 1, 1996 - two days before his death -

Jean Tabaud wrote to Father Edmund Cookson in the Altiplano of Peru

regarding the inheritance he was about to receive:

I trust you do

the best work possible to improve the life of those poor people

and the funds will be used wisely, in a solid practical way.

I like to imagine you standing in the bright sun of a pure

sky, fulfilled by the task of the day. You have a splendid life--

Signed: Jean

Later he made me promise,

"And, please, Elise, no prayers!" Jean had been born a

Catholic, and raised by the Jesuits, but following the death of

his father had never set foot in a church, of any kind, again. Shortly

thereafter, he made his exit from this world, as his father had

done before him: with a bullet in the head.

Despite

my promise, prayers were indeed said for Jean Tabaud by the population

of the distant city of Yunguyo in the Altiplano of Peru, on the

shores of Lake Titicaca. They took the form of a candlelight procession

to the top of the highest surrounding mountain, where a Requiem

Mass was said in remembrance of him. And following this, his photo

was placed in the 16th century cathedral of Yunguyo, which his money

helped to restore, and he is remembered in the daily prayers of

the congregation.

He died December 3, 1996. Eight years

later, when I began my research on his biography, I discovered the

following note among his papers. It was dated October 3, 1996:

For

many years now I have suffered from chronic Lyme disease, which

takes away all my strength. If the day comes when I no longer am

able to assume the chores around the house, rather than pay somebody

to do it for me - etc., etc. - I would chose to save the money for

the people I leave it to. This means that I'll have to die a little

sooner. With satisfaction.

|